Longing and Other Stories is a collection of three stories from Jun’ichirō Tanizaki, a prominent twentieth century Japanese writer. At only 148 pages, this collection is a short and breezy read that transports you to late 19th century and early 20th century Japan. Though all three stories explore the relationships between mothers and sons and the tensions of rapid modernization on a closely held culture, the stories are each distinct in genre and content.

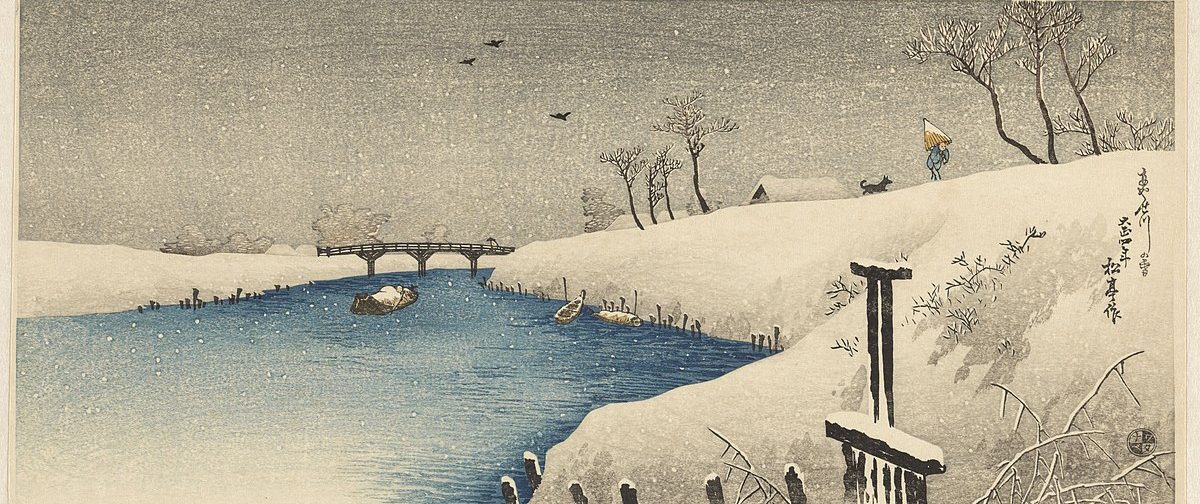

The title story “Longing” was my favorite of the trio, an account of a young boy’s walk home at night, replete with rich descriptions of nature. Tanizaki’s writing, and the accompanying translation, is particularly poetic and dreamy in this story, with the frequent use of repeated adjectives (“long long,” “slowly slowly,” “white, white,” etc) creating a sense of rhythm and emphasis. A repeated motif throughout the story is the long row of pine trees that lines the boy’s path. In the notes from the translator at the end of the book, it is stated that the pine trees have the same double meaning in Japanese as in English (“pine” can mean “to long” in addition to referring to a specific type of tree)– this is just one example of the cleverness and beauty of Tanizaki’s work. Reading this story felt like seeing traditional Japanese prints in motion.

The second story “Sorrows of a Heretic” follows an impoverished university student, who feels beaten down by his circumstances and unable to improvise his position.The narrator is profoundly unlikable and immoral, which is perhaps notable given that the translator notes emphasize the many autobiographical details of the story. In this manner, Tanizaki seems to exaggerate his own qualities that he deemed to be unfavorable, such as laziness, self-indulgent behavior, and apathy, as a way of engaging in self-reflection.

The final story “The Story of an Unhappy Mother” explores the theme of filial responsibility within the traditions of Confucianism, culminating in a conflict of loyalties between blood and marriage. Of the three stories, this one was the most driven by both plot and character. Though this story felt especially brief, the mother was depicted vividly with several anecdotes demonstrating the depth to which she experienced emotion, both the joys of life prior to and deep sorrow following a pivotal boating incident. This story succeeds in creating space for what is unsaid. By posing the direct conflict between a mother and spouse, Tanizaki created an unsettling moral dilemma that calls into question the cultural values we’ve each accepted as operable.

Overall, the collection was an enjoyable read that piqued my interest in reading more works by Tanizaki or other Japanese writers of his time.. As perhaps suggested by my thoughts above, the translator notes following the three stories are also not to be missed– absolutely wonderful insight that provides additional context on the stories’ histories.

Thank you to Columbia University Press and NetGalley for an ARC in exchange for an honest review.