Sonata per un mulattico lunatico.

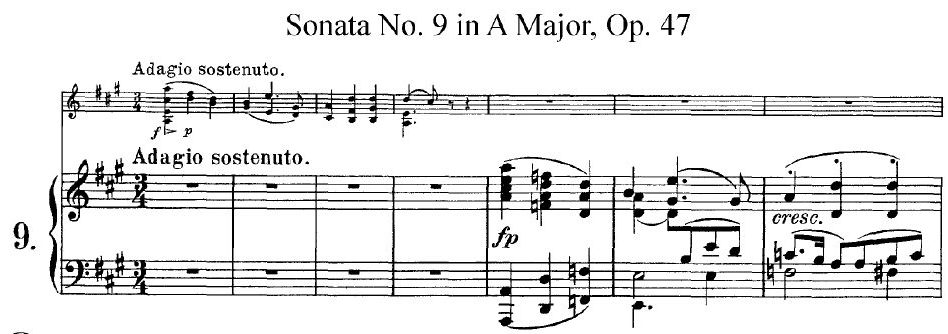

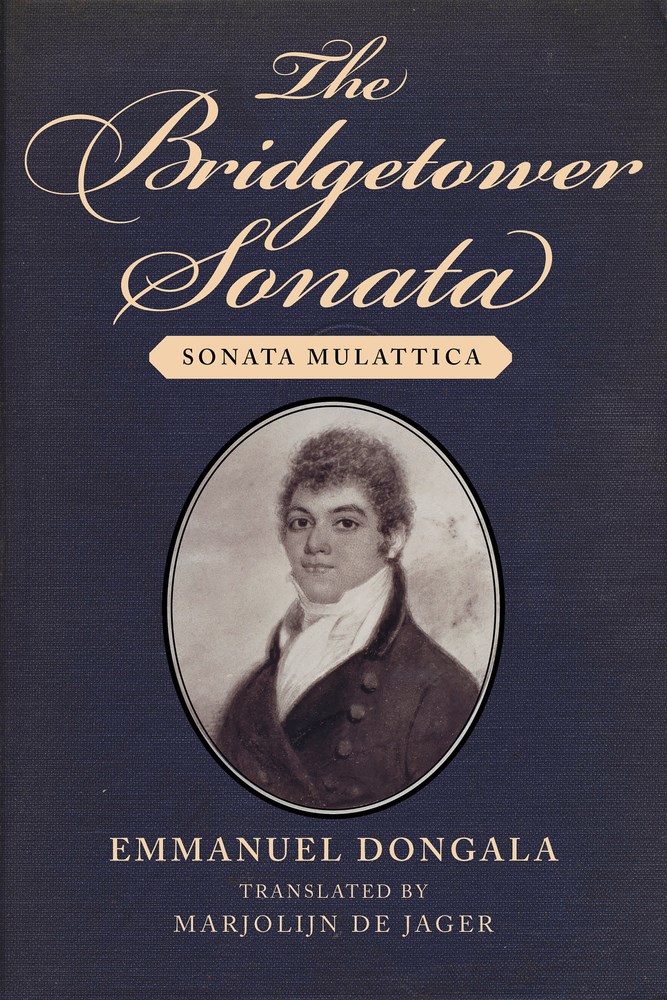

This is the dedication that Ludwig van Beethoven affectionately gave to his Violin Sonata No. 9, a piece deemed not only too hard to play, but also “outrageously unintelligible” and an affront to music, by contemporary virtuosic violinists. Due to a falling out, Beethoven ultimately rededicated the piece, leaving its original dedicatee largely lost to history.

The Bridgetower Sonata uses what is little known about George Augustus Polgreen Bridgetower to reconstruct a vivid imagining of his life leading up to his extraordinary friendship, and subsequent loss thereof, with Beethoven. Beginning with a slow, almost dry, descriptive chronology of George’s childhood and escalating to a swift telling of his early adult friendship with Beethoven, the novel provides an animated exploration not only of late 18th century race relations in Europe but also of the striking divisions in class that are coming to a head vis-à-vis the French Revolution. In a telling encounter with none other than Chevalier de Saint-Georges, perhaps more commonly remembered to the contemporary public as “Black Mozart,” George’s father John Bridgetower of West Indian origin, grapples with explaining that he is, in fact, George’s biological father. As described by the omniscient narrator’s divination into John’s thoughts, Europeans understood mulattos to be the by-product of a White father and mother of African origin. George’s dark skinned father and eastern European mother in itself challenged the chronicled systems of race in Europe at that time.

While perhaps the reconstructed meetings with iconic historical figures such as Thomas Jefferson, Angelo Soliman, Marquis de Lafayette, Théroigne de Mericourt, and Olympes de Gouges may be pure fantasy, they do help to further ground the story in its historical time period, providing essential context on how science, government, and civil code shaped the genre of music that is now loosely categorized as “Classical.” The cumulative result is the construction of a lively society of elitist figureheads bumping elbows, emphasizing the possibly factual notion that revolutionary-era people, at least in the upper classes, were largely “renaissance men” (and women)– highly cultured and thoroughly educated to a degree beyond our current imaginings.

As a violinist myself, I was enraptured by the descriptions of musical patronage and the coming together of notable musicians such as Mozart, Beethoven, Kreutzer, Haydn, and more. The rich narrative made me crave recordings of their compositions and has found me listening to an abundance of classical music in its wake.

As a whole, The Bridgetower Sonata is a delightful narrative helping to bring a forgotten story of a talented mulatto musician to light. While it explored interesting aspects of race in a historical context, it largely remained preserved in that historical bubble with little reflection on the current state of society and race relations. Similarly, the divide described between the old-school proponents of baroque music versus the latter-day proponents of classical period music easily draws parallels to current evolutions in popular music, but Dongala prefers to let history lay, allowing readers to draw their own conclusions. The book is by no means life-changing, but it’s a thoroughly entertaining read, particularly for admirers of classical music and revolutionary history.

Thank you to Inc. Shaffner Press and Above the Treeline for an ARC in exchange for an honest review.

TLDR: A delightful narrative about a young 18th century virtuoso violinist of mixed-race. Highly recommended for admirers of classical music and revolutionary history.