At the end of the book, I was left wondering who was the title beast? Alexander or Blanche? It was only in the days after as I continued to ponder that question that I stumbled across the original French title—as a novice student of French, I was struck by its gendered nature: Une Bête Au Paradise.

As perhaps the feminine noun “une bête” suggests (though this is more likely coincidental or may in fact be indicative of historical French views that civility is antithetical to femininity), the novel follows a female protagonist who is tormented by her love for the inarguably charming Alexander. The novel begins in the present with an elderly Blanche who is eerily alone as she wanders her ancestral farm.This opening scene provides a preview of what is to come as the novel quickly transitions into the past. Following a car crash that resulted in her parents’ death, 5-year old Blanche and her younger brother Gabriel are raised by their maternal grandmother Émilienne, a spirited woman who is largely defined by her resolute love of her farm, a plot in northern France that is aptly named Paradise. This brief look at her childhood quickly leads to a pivotal moment in which a dewey, teenage Blanche falls desperately in love with her classmate Alexander. Their relationship, though pure and earnest, quickly becomes clouded by Blanche and Alexander’s inability to reconcile Blanche’s refusal to give up her family’s farm with Alexander’s aspirations of a fresh start far from his childhood. As readers, we experience the ebb and flow of an ill-fit relationship over the course of two decades.

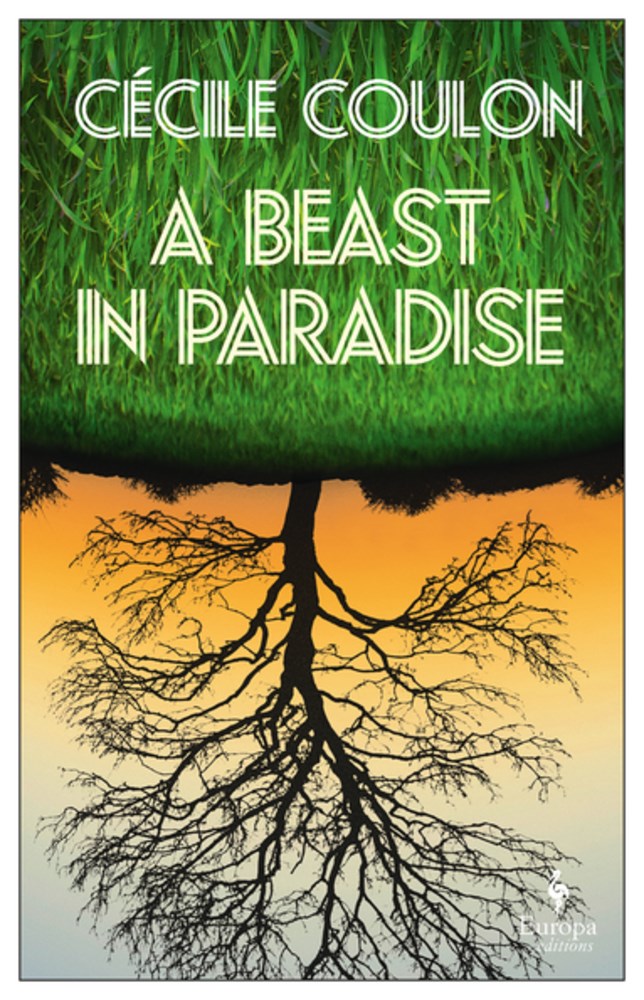

In this way, A Beast in Paradise is a saga of love and loss, colored with lush prose and a bold, unapologetic voice (“her contours molded by an endless series of deaths”), that seems to have been well-captured by translator Tina Kover. The epic and emotional narrative echoes the romantic novels of the late 18th century with tinges of the grotesque agricultural imagery that defines Marieke Lucas Rijneveld’s The Discomfort of Evening.

The parallel between beautiful language and visceral imagery serves author Cecile Coulon well, allowing her to deftly explore the feral nature of love and its ability to debilitate rational thinking. The lines between beast and man become both blurred and absurd as the characters grapple with their baser instincts while also acting as the arbiter of life for a slew of farm stock. Coulon openly invites the comparison between the characters and beasts, at times even drawing explicit metaphors between the two:

She went round and round in circles in that strange laboratory made of nothing, both the mad scientist and the guinea pig at once.

This book left me in awe and quite simply defines the kind of work I wish I could myself create. Especially considering it was released February 2, which happens to be my birthday, I have come to see it as a literary gift. I highly recommend this book, particularly to the literary-inclined, to lovers of words, and to those who may themselves be grappling with inner beasts.